The class struggle culminates in a single, clean, knockout punch. Their dedication and solidarity (as well as their reckless, good-timing approach to life, sex and art) stand in contrast to the greed and pretensions of the directors and producers, who lack vision, humanity and any sense of craft or fun. Hooper and his comrades are the unsung artists of the film industry, which regards them as expendable workers, to be exploited, endangered and cast aside. Reynolds’s Sonny Hooper is a stuntman - a perfectly meta role for an actor who had done his own driving while playing bootleggers, racers and other daredevils. Like many of his characters, he preferred to focus on getting the job done, and having as much fun as he could in the process. He was not the type of actor to take up causes or make political statements.

That kind of class consciousness would shift rightward in subsequent decades, an evolution that doesn’t really have much to do with Burt Reynolds. At the start of 1978, Johnny Paycheck’s version of David Allan Coe’s “Take This Job and Shove It” was the number one song on the country charts.

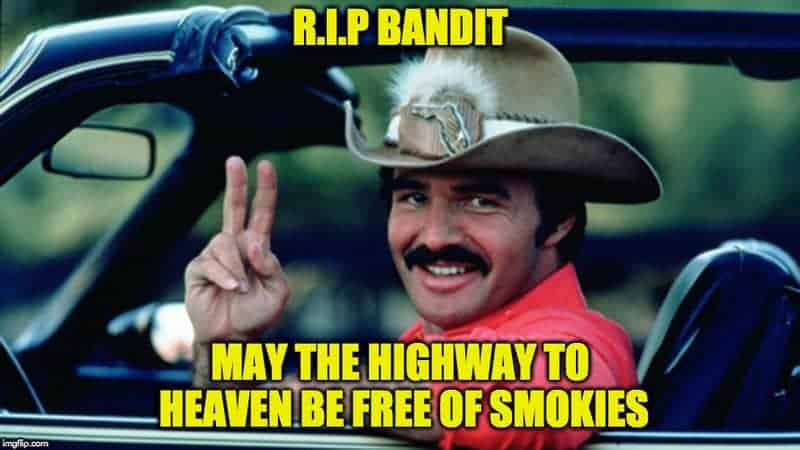

BURT REYNOLDS SMOKEY AND THE BANDIT LAUGH MOVIE

But more than any other movie star he embodied the stance that permeated much of the country-and-western and southern rock of the Carter era, in which regional pride and defiant hell-raising were accompanied - and sometimes drowned out - by class resentment directed against the bosses and their minions. I’m not saying Burt Reynolds (or Hal Needham, the director of “Smokey,” its sequels and others of its ilk) was a Hollywood Marxist. Cledus and Bandit are southern working-class white men in revolt against, to put it bluntly, state power and capitalist greed. It was also a protest movie, both widely popular and unabashedly populist, a word that meant something a little different back then. “Smokey and the Bandit” was - and remains - a hell of a lot of fun. Reynolds as Bandit, in that black Trans Am - was a genuine blockbuster four years later, finishing second in the year-end box office totals, after “Star Wars.” Reynolds’s high-octane, good-old-boy features, was released in 1973, the year the OPEC oil embargo began. Not in the movies themselves, of course, which screamed with Detroit muscle and reeked of burning petroleum. You might also remember gas lines, a stagnant economy and the growing popularity of lightweight, fuel-efficient, imported vehicles. But if you grew up in the prime of his stardom, you most likely remember him, with a mustache and a cowboy hat and maybe a pair of aviators, behind the wheel of a car. He was sometimes clean-shaven, and not always southern.

He could play romantic leads, detectives and football players: The range was always there, even if he didn’t always use it. The pride he took in performing his own stunts was partly the bluff machismo of a former athlete and partly a commitment to screen acting as a physical rather than a cerebral or emotional undertaking.

BURT REYNOLDS SMOKEY AND THE BANDIT LAUGH DRIVERS

Reynolds, who died Thursday, may not have lived up to his full potential as an actor - he often said so himself - but he was one of the great drivers in American popular culture. It’s fitting and consoling to imagine that he’s there now. Springsteen allows, might show up at that song’s titular automotive Valhalla. “Even Burt Reynolds in that black Trans Am,” Mr. Reynolds is inscribed in the automotive pantheon almost as an afterthought, following James Dean and the bootlegger Junior Johnson. In Bruce Springsteen’s “Cadillac Ranch,” Mr. Burt Reynolds had a way of being underestimated, even when he was being immortalized in song.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)